10 Jun Covid19 regularisation in Italy: a measure that did not lived up to its promises

Covid19 regularisation in Italy: a measure that did not lived up to its promises

By: Eleonora Celoria, Fieri

At the beginning of May 2020, exactly four years ago and in the midst of the spread of Covid19, the Italian government announced the regularisation of “essential” workers as a measure to respond to the ongoing pandemic.

The regularisation came after several years in which the practice of regularising migrant workers – a type of measure that had been frequently adopted in previous decades to tackle irregularity – had been put on hold. The new regularisation was presented as a way to address the crisis in the agricultural sector during the pandemic, to ensure that irregular migrants had access to health care, and to prevent the spread of the virus in the informal settlements where migrants were forced to live (EWSI, 2020). The Ministry of Agriculture and the law’s main promoter, Teresa Bellanova (then a member of the small centrist party founded by the ex-Prime Minister Matteo Renzi) justified the measure as a way to “guarantee adequate protection of individual and collective health” and “facilitate the emergence of irregular employment relationships” (HRW, 2020). The new proposal was thus based on a humanitarian narrative, that took into account the dignity of migrant workers.

However, four years after the announcement of the law, it has become clear that the Covid19 regularisation did not achieve the objectives set by the government and left many migrants in a state of legal limbo, further exposing them to insecurity and irregularity. To understand the reasons for this failure, it is crucial to look at the potential and actual beneficiaries of the law and its implementation.

The regularisation targeted all foreigners who had previously worked in the agriculture, fishing, care and domestic work sectors and who could prove to have entered Italy before the 8th of March 2020. The scheme was based on two different tracks. The first allowed employers to apply for the regularisation of their employees, both in cases where migrants had previously been employed in an irregular situation and where employers wished to employ them for the first time. The second track was aimed at those who have been living in Italy and working in one of the selected sectors, and whose permit to stay expired after October 2019: they could apply directly for a six-month residence permit to look for a job, without the mediation of their employer.

Immediately after the adoption of the regularisation decree, civil society organizations and scholars denounced that the scheme was too narrow but overly complicated, and that it contained too many rigid requirements and restrictions (Palumbo, 2020). With regard to the first track, the high number of requirements (related to financial resources and housing) that the employer had to fulfil acted as disincentive. Moreover, the cost of the regularisation amounted to 500 €, in principle due by employers but likely to be de facto (and illegally) charged on employees. On the other hand, the access to a direct application for regularisation was limited only to a small share of irregular migrants (those who became irregular from October 2019 onwards).

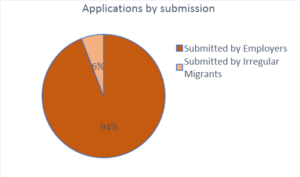

Overall, 208,000 people applied for the regularisation, out of an estimated stock of 690,000 undocumented immigrants (ISMU, 2020), during a two-months period in the summer of 2020. Of the total number of applications, 207,542 were submitted by employers and only 12,986 were submitted directly by irregular migrants under track 2 of the programme (Ministry of Interior, 2020).

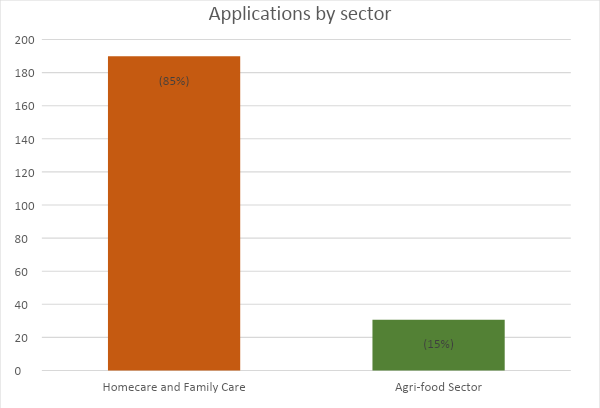

85% of the applications were in the homecare and family care sector, while only the 15% (30,694) regarded migrants employed in the agri-food sector. Such data immediately suggests that the regularisation has had very marginal consequences on the conditions of migrants exploited in the fields and forced to live in informal settlements with little access to services and healthcare.

The very low number of applications made directly by undocumented migrants shows that the chances to regularise remained largely dependent on the employers. In the agricultural sector, they had necessarily to be registered companies, and to disclose their financial situation. For this reason, the measure was not appealing for many farmers who did not intend to declare previous irregular jobs nor to hire irregular migrants, as proved by the low number of applications in this sector. Moreover, in a sector where workers move frequently on the territory according to the harvest seasons, and that is affected by the widespread system of gang mastering (caporalato) the workers may not even be aware of who their employer is. On the contrary, the higher rate of applications in the domestic sector can probably be explained by the fact that employers in this sector are mainly private individuals or families, who may have a closer personal relationship with the irregular worker. According to AltraEconomia, there is a strong probability that many of the applications were based on a “fake” work relationship between the employer and the worker, based on the formal existence of the contract and the payment of social benefits (a cost that is normally sustained by the worker), even though the migrant does not actually work for the fictional employer (Altraeconomia, 2021).

Beside the critical remarks related to the “flop” of the regularisations among agri-food workers, the inadequacy of the policy as a tool for safeguarding the dignity and right to health of irregular migrants has also become apparent during the implementation phase. In fact, even those who applied for regularisation, did not immediately obtain a permit to stay. As a consequence, only in some Regions the migrants were fully covered by the National Health System, while in others they only received necessary an emergency care (including Covid vaccinations). The law was implemented by local officials of the Ministry of the Interior (within the “Prefetture”), who had to carry out the necessary checks before granting a residence permit (then issued by local police headquarters, the Questure). As with previous regularisations, the process proved to be particularly cumbersome, and all preliminary checks had to be carried out in person: at a time when freedom of movement was severely restricted due to the Covid, such a solution slowed down the process. Finally, it was not until May 2021, a year after the law was announced, that new staff were recruited to carry out the assessments: the chronic understaffing of the Prefetture was one of the main reasons for the delays in the process.

As of April 2021, in fact, out of a total of 200,000 migrants who had applied for a permit under the regularisations scheme, just 11,000, or 5%, had received one (Ero Straniero, 2021). At the end of March 2022, almost two years past the adoption of the law, only 104.948 applications were processed, but not all of them immediately resulted in the issuance of the permit to stay by police headquarters. (Ero Straniero, 2022). According to the last report published in 2023 by the coalition Ero Straniero, thousands of applications still remained to be processed three years from the beginning of the implementation of program. In the meanwhile, the temporary workers appointed to deal with regularisation files in the Prefetture were dismissed in December 2022. The situation was particularly serious in the largest cities, such as Milan and Rome, where the highest number of applications had been submitted. In Milan, out of 26,225 applications, only 13,146 were processed by the Prefecture (of which 2,370 were rejected). However, the Police Headquarters issued only 6,784 residence permits, barely 25% of the total number of applications submitted. In Rome, out of 17,371 applications, only 9,151 files had been finalised, just over 52% of the applications received. During the implementation phase, thus, an implicit obstruction policy was put in place at both the central and the local level of the administration, in order to delay the procedures and to deter the employers from finalising them.

The severe delays left most of the applicants in a legal limbo, denying them full access to social rights such as health care or unemployment benefits. Migrants remained linked to the same employers that submitted the initial application until the final release of the permit to stay: either they had to continue working for them, or, if they wanted or needed to change the employer, they had no other chance but to work irregularly. Their dependence on a single and fixed employer (which could also be a “fake” one) and the impossibility to leave the “limbo” in which they were constrained increased, in many situations, the vulnerability of workers to exploitation (PICUM, 2021). Against this background, civil society actors (united in the advocacy coalition “Ero Straniero”) have repeatedly urged the government to speed up the procedures, but, since their demands were only partially met, some NGOs decided to bring the Prefetture of Milan and Rome before the courts, together with several migrants affected by the delays.

Two collective complaints were filed before the administrative courts in Rome and Milan by hundreds of workers and several NGOs (including CILD, Asgi, Oxfam Italia, Spazi Circolari). While the administrative Court in Rome dismissed the case on the ground that the delays were justified by restrictions imposed by the pandemic (the decision was then appealed before the Council of State and the proceeding is still pending), the Court in Milan recognized that the legal deadlines for adopting a decision in immigration matters had been abundantly exceeded, and ordered the Prefecture in Milan to process the remaining applications within 90 days. As of April 2024, 3,500 files still needed to be processed, and thus the Associations have asked the Judge to appoint a substitute commissioner which could replace the Prefecture in dealing speedily with the applications, a tool that it has not been widely used in the field of migration. The collective actions have proved to be an important tool for both individuals and civil society organizations representing migrants’ interest to limit administrative discretion (for example, in terms of the time taken to issue a final decision) in procedures affecting fundamental rights. Nonetheless, in the fourth anniversary since the adoption of the regularisation law, several applications (in Rome, but also in Turin or Naples) are still to be examined.

Our analysis suggests that the measure, while benefitting irregular migrants employed working in the domestic sector, did not contributed to the reducing the exploitation in the agri-food sector, nor to the enhancement of the dignity of irregular migrant workers involved in the regularisation process. As for the main reasons that explain the partial failure of the measures, we could point to the following elements: first, as reported by many commentators, the program was overly complicated, with rigid requirements and restrictions, and such a complexity made it difficult for both employers and migrants to navigate the process effectively. Second, a delay strategy was put in place at the national and local during the implementation of the mechanism, with the result of deterring the employers from finalising the procedures. Third, while the plan allowed migrants to apply directly for regularisation, this option was only available to a small sub-category of irregular migrants (those who fell back into irregularity after October 2019 due to the expiry of a pre-existing residence permit). This meant that the majority of applications came through employers even tough previous regularisations already proved the limited availability of employers in the agricultural sector to engage with these programs (ISMU, 2020). Third, the huge delays in the processing of application forced migrants to remain dependant on their employers and, especially in the cases when the latter were not “genuine” and migrants had to pay for the regularisation, this implied increased exposure to accept the working conditions imposed on them, even when amounted to exploitation.

To conclude, it is important to stress that regularisations are not an intrinsically problematic policy tool. However, their potential to safeguard the dignity of workers and to prevent exploitation depends on the way the law is framed and on the degree of dependence on employers created by the program: the more migrants are recognised agency and direct control over the regularisation procedure the less they are exposed to exploitation and the highest the emancipatory impact of the regularisation scheme.

Latest News

- The Sevilla Manifesto: Voices of migrant workers from Sevilla and beyond

- “From Being Studied to Leading Change”. Participatory Action Research as a Transformative Political Tool

- Morocco-EU Relations: What’s at Stake for Farm to Fork Workers? Social Transformations and Food Security

- Examining migration and work precarity: what is the added value (and potential downside) of a public health perspective?

- The UIZ (Université Ibn Zohr) team met the socialist group at the parliament in Morocco